By Dr. Rob Kevlihan, Consultative Director, Shanahan Research Group, Dublin and Rachna Shanbog, PhD Research Fellow, Dublin City University. [1]

Introduction

‘U.S. provides nearly $5.9 million in health assistance to India on COVID-19’ read the 17th April 2020 headline in The Hindu newspaper. Three days later another headline in The Diplomat stated ‘India’s COVID-19 cooperation with the Middle East’. The most recent development in this sphere has been India sending doctors and nurses to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in response to them sending medicines to India.

As part of its humanitarian effort during COVID-19 times, India has despatched the hydroxychloroquine drug to 55 countries, while also sending testing kits and healthcare workers, as well as other assistance (including wheat), to countries such as Afghanistan. This assistance has been provided despite pressing domestic needs in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and weak public health systems in many states (Kerala being a notable exception), that includes a scarcity of testing kits, shortage of health care workers, a paucity of protection gear (including masks and other personal protective equipment for health care workers), limited flow of funds from the central government to some state governments and the economic effects of a sudden and prolonged lockdown on migrant workers (leading to shortages of food, etc). In return international donors, including USAID, the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and countries such as the UAE have offered either medical aid or financial grants and loans to help India in its fight against the pandemic and to strengthen the health care system in the country.

This post highlights the international humanitarian efforts the country has undertaken and considers possible reasons that may influence India’s decisions to provide international humanitarian assistance despite a very challenging domestic situation.

A brief history of India’s ODA

India has been an aid donor for over 50 years. Its overseas aid programme was greatly expanded around the turn of the century, reflecting the country’s growing importance as an economic power more generally.

From the literature, one can trace the beginning of the first phase of the aid programme to the Asian Relations Conference conducted in Delhi in March-April of 1947. The focus of the conference, which was held just a few months before India gained independence (on 15th August 1947), was to bring together neighbouring countries of the south and to create a platform for common sharing and learning. The first formal Indian aid scheme to be established (which continues to operate to the present day) was the Indian Technical & Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme which commenced in September 1964, providing scholarships for students from overseas to study in India. The ITEC programme along with the Special Commonwealth African Assistance Programme (SCAAP) dominated India’s foreign aid until the early 2000s. This changed from 2003 onwards, when the then Finance Minister, Jaswant Singh, announced in the Indian Parliament that the country would not continue to take aid from countries other than a handful of nations and that it would intensify its own overseas development aid programme.

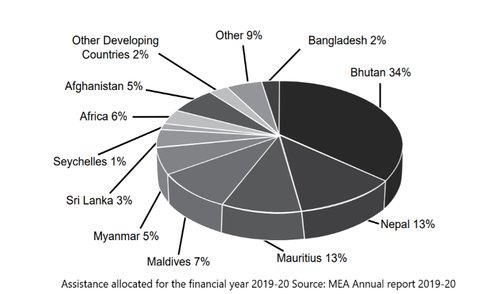

This change in policy resulted in a large expansion in overseas aid and a change in emphasis to include increased concessional lending, large infrastructure projects and support to overseas aid projects across a range of sectors, including support to UN agencies, and bilateral project-based aid in partner countries. The bulk of this development assistance has been focused on India’s immediate neighbourhood, with countries such as Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and the Maldives amongst the largest single recipients.

This change in policy resulted in a large expansion in overseas aid and a change in emphasis to include increased concessional lending, large infrastructure projects and support to overseas aid projects across a range of sectors, including support to UN agencies, and bilateral project-based aid in partner countries. The bulk of this development assistance has been focused on India’s immediate neighbourhood, with countries such as Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and the Maldives amongst the largest single recipients.

While aid to individual African countries is relatively modest (with the notable exceptions of Indian Ocean states Mauritius and Seychelles), African states in aggregate (defined as African Union member states, including island states) receive the second-highest level official development assistance from India after Asian states. Competition with China, the need for raw materials and resources such as oil, and access to markets for Indian products have led India to use ODA as a tool for better foreign relations in Africa (Agrawal, 2007, p. 7). Further, changes in the nature of development support to African states have been attributed to India seeking access to new markets, ensuring access to resources such as oil, and in order for India to gain the support of the African states in international fora (Mullen et al. 2014).

Indian Humanitarian Aid modalities

The information in the pie chart above draws from official reports presented by the Indian government. Official India aid statistics do not disaggregate the value of humanitarian aid it provides as part of its official statistics, despite including it as a category within the components of its overall aid.

While disaggregated information on its development aid programme undoubtedly captures some of its contributions to disaster-affected countries (e.g. support for housing projects in post-conflict Sri Lanka) that are funded from its Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget, this does not reflect all the assistance India provides in response to disasters. In recent years, for example, India assisted Sri Lanka during the Tsunami in 2004 and in response to severe flooding in 2016; provided emergency assistance to Nepal in the wake of the earthquake in 2015; has supported refugees from the North Rakhine State in Myanmar in the last few years; and also provided earthquake relief to Indonesia in 2018.

In providing this assistance, India typically utilizes bi-lateral channels, handing over funds and material to recipient states to undertake the relief work or by initiating project work through grants (usually managed by its local embassy). Despite having a strong civil society sector domestically, India does not support Indian NGOs to carry out humanitarian or development work in other countries and largely does not leverage the experience of its domestic NGOs in its overseas aid programme. This helps India in keeping closer state-state ties with recipient states and their bureaucracies not just at the national level, but also at sub-national levels, increasing the space for influence. Furthermore, India as one of the leading development partners of states in the Global South follows South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC) principles. These principles have, from the beginning, emphasized the need to meet recipient needs rather than dictating how assistance to be used, and as such can in some respects be thought of as precursors to more recent efforts by the international humanitarian aid system to focus on localisation of implementation.

Determinants of Indian overseas aid

While there is no one single determinant of Indian overseas development assistance, a number of related motives appear to play a role in aid decisions. Over the long term, India’s support to neighbouring countries, following its so-called neighbourhood policy, is something that has been a consistent part of India’s foreign policy since independence.

This support can be attributed to both altruistic and self-interested motives. For one, South-South Development Cooperation (SSDC) has long played a significant role in guiding India’s foreign policy, with overseas aid perceived by successive governments as a soft power tool. India has an interest in maintaining peace and stability in its neighbourhood, driven by what could be described as enlightened self-interest. India has also led in efforts to address other significant health challenges, despite domestic needs, in what is described as goodwill gesture.[2] Those of a more realist disposition also point to Indian wariness of growing Chinese influence, especially in the South Asian region in recent decades.

More recent developments have seen other domestic considerations impacting on India’s approach to international co-operation. Increasing violence against Indian Muslims, the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 and of the National Register of Citizens was followed (in late 2019) by nation-wide protests that received global attention, potentially damaging India’s image not just as the largest democracy, but also as an emerging power. Aid to neighbouring countries (particularly neighbouring Muslim majority states) can work to counter criticisms of the government’s treatment of minorities domestically.

One example is the assistance provided to UAE mentioned at the beginning of this piece. Soon after this support was provided, for example, UAE, together with some other states (including the Maldives, which is a large long term recipient of India overseas assistance) supported India when Pakistan took up the issue of growing Islamophobia in the country at an Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC) meeting in late May. Indian aid efforts represented something of a ‘two for one’ in this instance, as the UAE is also a host to as many as three million Indian migrants, representing the single most important overseas source of remittances to India in 2018.

Beyond specific concerns with respect to the UAE, India’s recently successful push for a seat on the UN Security Council created further incentives for the country to be seen taking a leadership role internationally. “Pandemic has reinforced India's image as a very responsible international stakeholder” said the Indian Ambassador to Morocco in a recent interview. Supporting a large number of countries during this global crisis helps India to continue building its image as an emerging leader.

Additional possible humanitarian initiatives

India does not have a strong culture of strategic planning when it comes to its overseas aid. Future plans and directions can therefore be difficult to predict and can often be a result of the initiative of senior political figures in the government.

One recent suggestion that has emerged from India’s Minister for External Affairs, Dr. Jaishankar, with respect to the current pandemic has been the possibility of using India’s ITEC programme to invite foreign experts to come to India to exchange their experience and best practices of dealing with COVID-19. Adapting ITEC, the oldest form of Indian aid, to the current global situation, will facilitate experts from overseas to be brought into the country, enabling cross-learning. It could also enhance the skills of medical workforces in recipient countries through e-ITEC. If one were to look for a pattern in the recent tweets by the minister, the ITEC programme has been particularly mentioned as one of the tools to build relations between India and South American countries, and as such, may represent an effort to extend the country’s influence beyond Asia and Africa.

Concluding thoughts

The absence of a cohesive Indian government policy (including a written guiding strategic framework) and nature of India’s bureaucratic apparatus with respect to its overseas humanitarian assistance mean that Indian assistance to other countries in times of disaster is frequently ad hoc and reactive.

This is not a result of deliberate calculation, but rather a consequence of ambition outstripping bureaucratic and management systems and processes. The operational effectiveness of India overseas assistance, including humanitarian assistance, could certainly be strengthened by the adoption of a more thought through approach that coordinates the management of this assistance within the bureaucracy, works to strengthen mechanisms for oversight and evaluation and ensures that all humanitarian aid provided by the government is recorded and separately categorized in reporting of ODA. Such efforts will need to be supported by further increases in staffing within the aid bureaucracy, particularly in the foreign ministry. Despite recent efforts to bridge a staffing gap, staffing levels within this ministry are low compared to the scale of the challenges facing the country.

More broadly in disaster-affected countries (or countries frequently subject to certain kinds of natural disasters) where India also has a development aid presence, the overall effectiveness of Indian aid would be greatly strengthened by joined-up thinking that includes planning around use of development funds for disaster preparedness, disaster response and post-disaster recovery. This would require, however, a greater focus at both Delhi and embassy levels on strategic planning, performance measurement and evaluation of overseas aid, all areas that have been relatively neglected within India’s aid architecture to date.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr Rob Kevlihan is Consultative Director of the Shanahan Research Group (formerly known as the Kimmage Development Studies Centre) and Managing Director of Gumfoot Consultancy Ltd, a private consulting company specializing in advising governments and development organizations on governance, compliance and risk. Prior to joining KDSC in 2014 he worked for more than 15 years as a scholar, researcher and practitioner on development, humanitarian action, and conflict themes in Africa and Asia. He has a PhD in International Relations from The American University in Washington, D.C.

Rachna Shanbog had been working in the development sector in India for the last nine years before she joined DCU in September 2017. She has worked with organisations such as UN Women India, The Huner Project (INGO), and other various organizations at the national level on issues concerning women and children. As one of the five Early Stage Researchers on the Marie Skłodowska-Curie ETN on Global India, at the Ireland India Institute at Dublin City University, Rachna will undertake her PhD on ‘India’s foreign aid policy’.

Footnotes

[1] This work was supported by Marie Sklodowska-Curie European Training Network titled “Global India” that aims to create the knowledge and expertise required for the EU’s engagement with India (www.globalindia.eu) (Grant Agreement 722446). The training network is funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme.

[2] Journalists reporting on public health issues in India have questioned the government on why it was exporting medicines to other countries (including the US), despite shortages of these same medicines at home. An article by Aljazeera highlighted how an Indian made anti-malaria drug has become a tool of Indian diplomacy. Donations of medicines have been described by one Indian diplomat as goodwill gestures, especially because these medicines are sent to countries (such as African states, BRICS [Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa] nations) which have strategic partnerships with India.

Image by DARSHAK PANDYA from Pixabay

DSAI provides a platform for dialogue for development studies research, policy and practice across multi-disciplinary perspectives. This opinion piece is published as part of DSAI's call for contributions to our COVID resource section; as a space for pooling and sharing knowledge. Content is published with permission of the author. Views expressed are the authors' own.